The Complexity We Designed Into Our Lives

In 2007, I was diagnosed with Lupus. I was in my early twenties, working in tech, and had no idea how to live healthily. I didn't know how to be active, eat well, or recognize when my body needed rest. These weren't things I'd learned growing up.

When Fitbit launched, I was the perfect target customer: young, tech-obsessed, newly health-conscious, and desperate for answers. Surely data could solve this.

Over the following years, I became a walking Wirecutter for activity trackers. Fitbit to Nike Fuelband to Jawbone UP to Withings to Apple Watch. Each promised the same thing: tracking your data will make you healthier.

The Big Data Era

This was the age of Nicholas Felton's annual reports—beautiful, exhaustive visualizations of personal data modeled after corporate annual reports. The design world was infatuated. The promise was seductive: collect enough data and you'll understand yourself.

We believed more data meant more insight. More sensors, more tracking, more quantification. We gamified steps, sleep cycles, and heart rate variability. We turned our bodies into dashboards.

But we learned something uncomfortable: data doesn't automatically become knowledge. We had gigabytes of information about ourselves, yet somehow understood ourselves less. Now we're being told AI will fix this—that algorithms will tell us what our data means.

The Creep of Complexity

Technology designed to simplify our lives has made them more complicated.

Cars are a perfect example. We've made them safer for occupants and more deadly for everyone outside. We've replaced a century of thoughtful UX refinement—physical buttons, tactile feedback, spatial memory—with touchscreens that demand visual attention. We've added complexity in the name of features.

This pattern is everywhere. Washing machines connected to the internet. Smart refrigerators. Devices that require apps, accounts, updates, and constant attention. We've created *mental sludge*—a layer of digital maintenance tasks that accumulates in our lives, demanding to be tended.

Each notification is a small interruption. Each app is a small relationship to maintain. Each connected device is a small responsibility. Individually manageable. Collectively suffocating.

Subtracting Back to Clarity

I find myself yearning for constrained communication. A rotary phone plugged into the wall without an answering machine—if I'm home, I'll answer. If not, try again later. A PO box for letters that arrive on their own schedule, not mine.

I've stopped wearing a smartwatch.

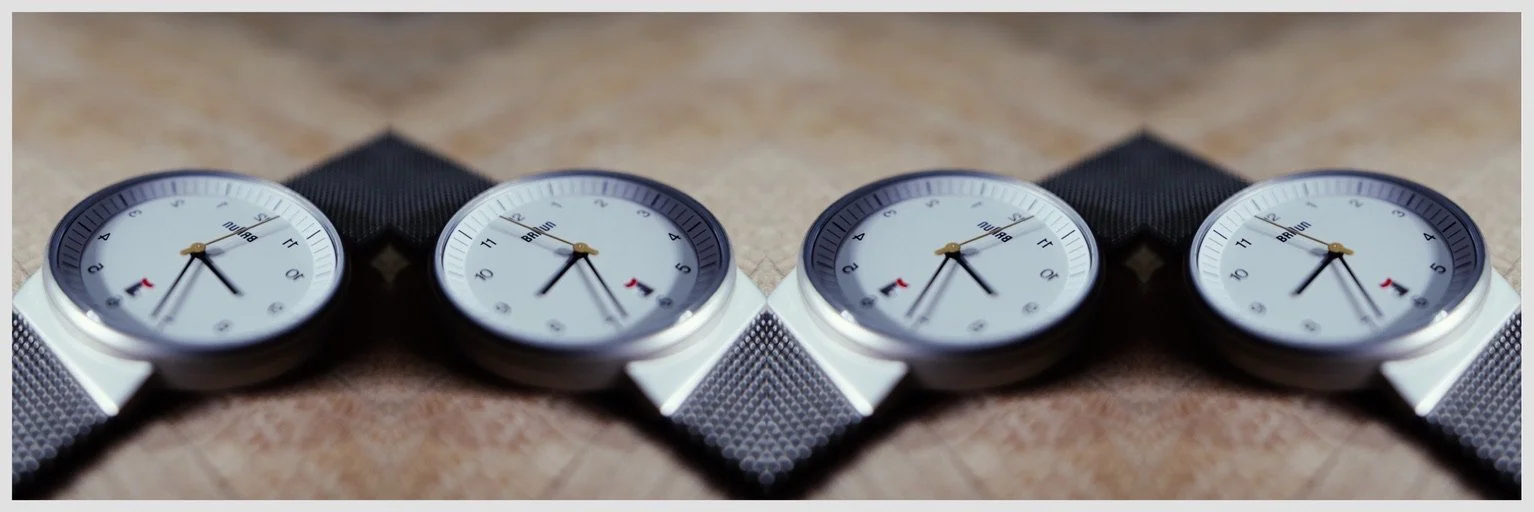

I now wear a classic watch designed by Dieter Rams. It tells me the time and the date. That's it. It doesn't buzz. It doesn't interrupt conversations. It doesn't require daily charging. When I glance at it, I'm not bracing for a barrage of notifications.

It does exactly what a watch should do, and nothing more.

What We've Forgotten About Good Design

Dieter Rams's tenth principle of good design is that good design is as little design as possible. We've spent the last fifteen years doing the opposite—adding features, collecting data, creating "ecosystems" that lock us into complexity.

Good design should reduce cognitive load, not increase it. It should clarify, not obscure. It should serve human needs, not create new dependencies.

I spent years believing that more data would help me manage a chronic illness. What actually helped was learning to listen to my body, understanding my limits, and building sustainable habits. The data was noise. The insight came from attention.

Designing for Less

As designers, we're often measured by what we add—features shipped, interactions designed, data visualized. But maybe the more important question is: *what can we remove?*

There seems to be a trend back to simplicity. What if we treated people's attention as the finite resource it is? What if we acknowledged that complexity has a cost, and sometimes the most valuable thing we can give someone is simplicity?

We've lost something in our rush to digitize, quantify, and connect everything. We've forgotten that constraints can be liberating. That doing less can mean living more.

My watch tells me the time. That's all I need it to do.